To be, or not to be: that is the question:

Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them? To die: to sleep;

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to, 'tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wish'd. To die, to sleep;

To sleep: perchance to dream: ay, there's the rub;

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause: there's the respect

That makes calamity of so long life;

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

The oppressor's wrong, the proud man's contumely,

The pangs of despised love, the law's delay,

The insolence of office and the spurns

That patient merit of the unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscover'd country from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all;

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pith and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action.

Hamlet by William Shakespeare

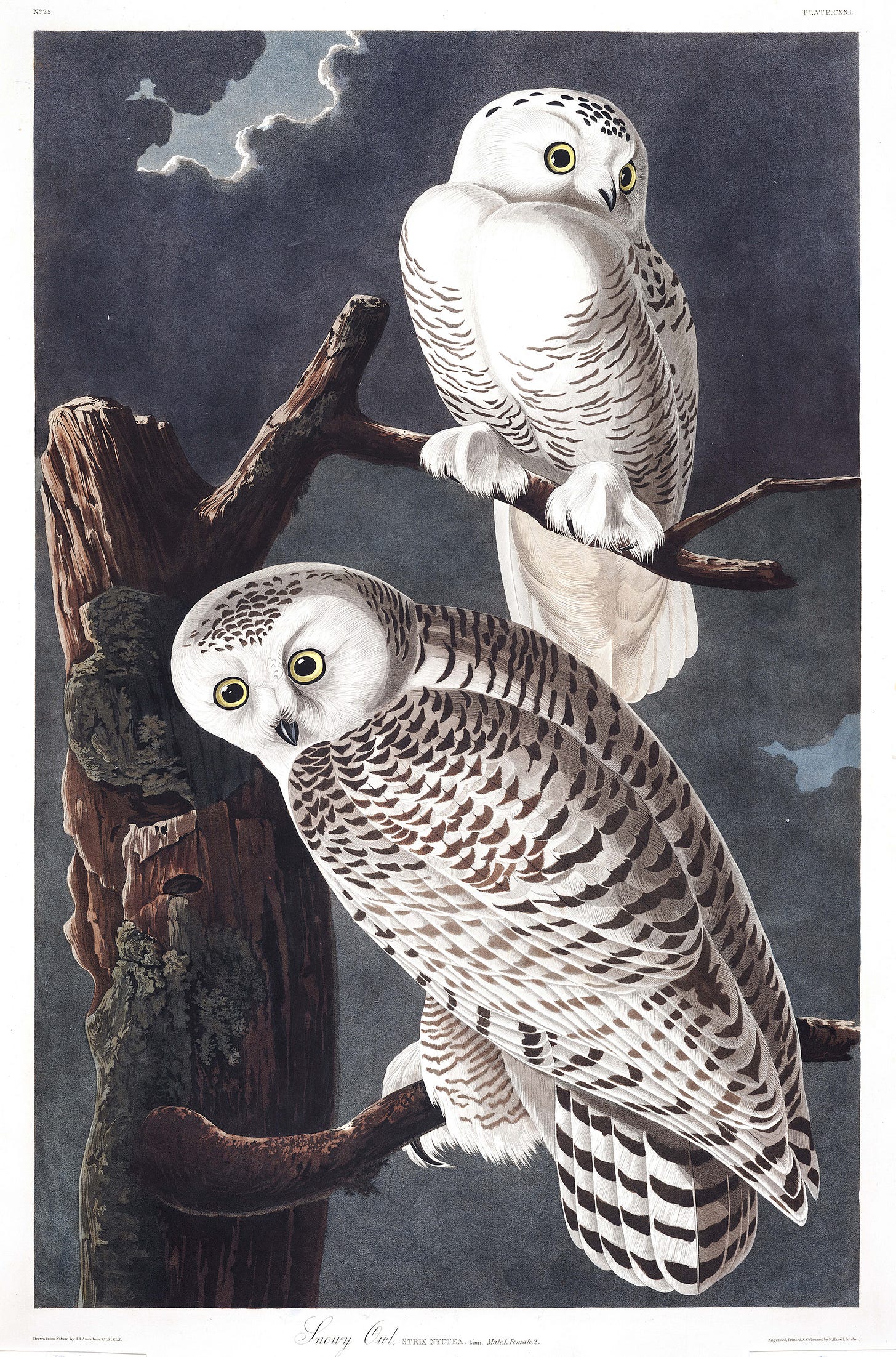

OWL

The first documented image of an owl is in Chauvet Cave, France, and is about 30,000 years old. The owls are nocturnal hunters, they rarely appear in the day, but when they do, they seem to look at us with a strange, high-intensity attention. They have a sharp view and can turn around 240 degrees, some human observers have made the mistake of reporting a complete circular rotation of 360 degrees. Owl’s special traits are ideal for making it the image of penetrating consciousness —the visionary in the middle of darkness— and at the same time, it embodies the power of death as an unexpected visitor at night. In Greek mythology, the owl is the bird of Athena, goddess of wisdom, the arts and techniques of war, as well as the protector of the city of Athens and the patron saint of artisans. Athena's owl is usually featured in Western culture as a symbol of philosophy. In the Egyptian hieroglyphic system, the owl symbolizes death, cold and passivity. Germanic and Eastern European cultures, and Chinese ancestral traditions, see the appearance of the owls as a sign of bad omen and imminent death. The owl is also a friend of the magician world, witches and it appears as a guiding spirit of the Siberian and Inuit shamans.

“The word itself is invisible, but it has become visible and can be seen in the works of the creator. The world is a book written by the finger of God, and each creature is a letter of God, so to speak. Therefore, mortal man, when he I looks at the world, is like an illiterate man who looks at a printed page, for it conveys no sense to him. He only secs the outer forms, but has no eyes for the eternal idea expressed in it. It is, therefore, man’s duty to learn to read the book of the world.”

Barbara Hannah in Encounters with the Soul: Active Imagination as Developed by C.G. Jung

Ser o no ser, aquest és el dilema:

¿és més noble sofrir calladament

les fletxes i els embats d’una Fortuna indigna,

o alçar-se en armes contra un mar d’adversitats

i eliminar-les combatent? Morir, dormir: res més...

I si dormint s’esborren tots els mals del cor

i els mil estigmes naturals heretats per la carn,

¿quin desenllaç pot ser més desitjat?

Morir, dormir... dormir... i potser somiar...

Sí, aquest és l’obstacle: no saber

quins somnis acompanyaran el son etern,

un cop alliberats d’aquesta pell mortal,

És el que ens frena i fa que concedim

tan llarga vida a les calamitats.

¿Per què aguantem, si no, l’escarni d’aquests temps,

El jou dels opressors, el greuge dels superbs,

l’amor burlat, la lentitud de la justícia,

l’orgull de qui té un càrrec o el desdeny

dels ineptes pel mèrit pacient,

quan un mateix pot liquidar els seus comptes

amb una simple daga? ¿Qui arrossegaria

El pes d’aquest bagatge tan feixuc

tota una vida de suors i planys,

Si no fos que el temor d’alguna cosa

més enllà de la mort, aquell país inexplorat del qual

no torna mai cap viatger, confon la voluntat

i fa que preferim patir mals coneguts

a fugir cap a uns altres que desconeixem?

I així la consciència ens fa covards a tots,

els colors naturals del nostre impuls

empal·lideixen sota l’ombra de la reflexió,

i empreses de gran pes i gran volada

per aquesta raó desvien el seu curs, i perden

El nom d’accions.

Hamlet de William Shakespeare (traduït per Joan Sallent)

MUSSOL

La primera imatge documentada d’un mussol es troba a la cova de Chauvet, a França, i té uns 30.000 anys. Els mussols són caçadors nocturns, rarament apareixen de dia, però quan ho fan semblen mirar-nos amb una atenció estranya, d’alta intensitat. Tenen una aguda visió i poden girar el cap 240 graus, alguns observadors humans han comès l’error de reportar un gir circular complet de 360 graus. Les característiques especials del mussol són ideals per convertir-lo en la imatge de la consciència penetrant, el vident enmig de la foscor, i a la vegada, encarnen el poder de la mort com a visitant furtiu en plena nit. En la mitologia grega, el mussol és l'au que acompanya Atenea, deessa de la saviesa, les arts i les tècniques de la guerra, a més de la protectora de la ciutat d'Atenes i la patrona dels artesans. El mussol d'Atenea sol aparèixer en la cultura occidental com a símbol de la filosofia. En el sistema jeroglífic egipci, el mussol simbolitza la mort, la fred i la passivitat. Les cultures germàniques i de l’Europa de l’Est, i les tradicions ancestrals xineses, veuen l’aparició dels mussols com auguris funestes i de mort imminent. El mussol també és amic de les bruixes, el món de la màgia i apareix com a esperit servicial dels xamans siberians i inuits.

“La paraula en si és invisible i només pot veure's a través de les obres del creador. Per dir-ho d'alguna manera, el món és un llibre escrit pel dit de Déu i cada criatura és una lletra escrita. Així, l’ésser mortal mirant al món és com un illetrat mirant una pàgina impresa incapaç de desxifrar-ne el significat. Només veu la forma exterior, no té ulls per a veure la idea eterna expressada en ella. Llavors, la tasca de l'ésser humà consisteix a comprendre el llibre del món.”

Barbara Hannah a Encounters with the Soul: Active Imagination as Developed by C.G. Jung