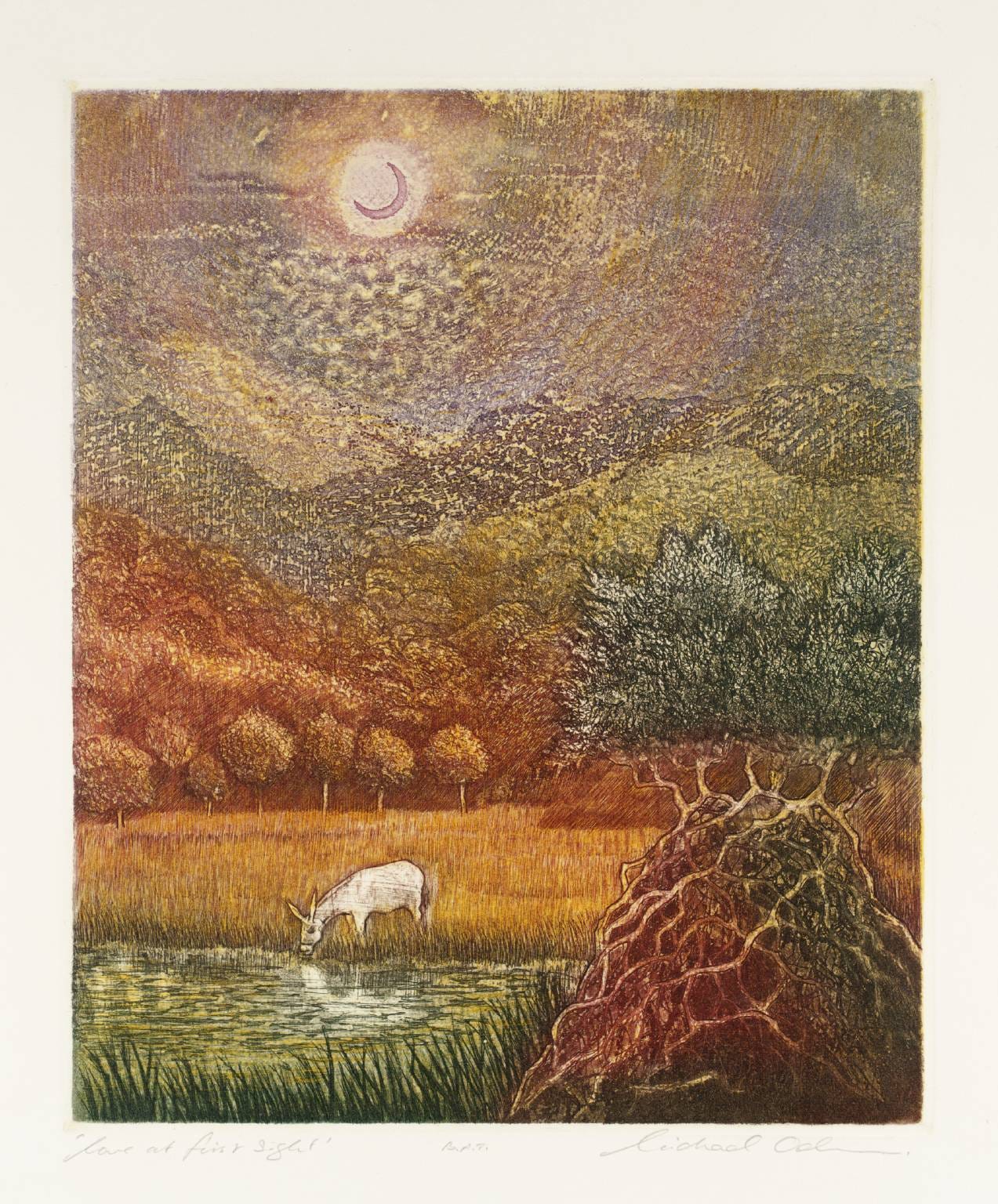

#37. DONKEY / BURRO

An if we live, we live to tread on kings. / Si vivim, visquem per aixafar el rei.

O gentlemen, the time of life is short;

An if we live,

we live to tread on kings.

Henry IV by William Shakespeare

DONKEY

Donkey’s tenacity is legendary, but in the collective imaginary of many cultures it is the image of ignorance. In Ancient Egypt, the red donkey was one of the most evil entities hindering the journey of the soul to the afterlife. The Golden Ass by Apuleius illustrates the vision of the donkey as the incarnation of the lowest instincts in contrast to spiritual elevation: Lucius turns into a donkey and only when he returns to his human body can he follow the path to salvation. Renaissance painting materialized laziness, stubbornness, incompetence, and blind fidelity in the form of the donkey. Donkeys are also linked to the buffoons, carnivals, orgies of Dionysius and the medieval saturnalia where the conventional order of things was reversed. Alchemy associated the donkey with the demon of three heads —mercury, salt and sulfur— the three material principles of nature and saw the wild donkey as a telluric and redemptory spirit. What if we have projected the image of ignorance into an animal that treated with love is persistent and affectionate? Donkey’s humility, good humour and diligence to face adversity may make him an enjoyable companion. In the Bible, the donkey is usually a symbol of peace, poverty, patience and courage: a donkey makes Balaam see that the Jehovah angel has arrived; Joseph goes to Egypt riding a donkey to escape King Herod's wrath and Jesus rides a donkey into Jerusalem in his triumphal entry.

“Through pride we are ever deceiving ourselves. But deep down below the surface of the average conscience a still, small voice says to us, something is out of tune.”

C. G. Jung

Senyors, el temps de la vida és breu…

Si vivim,

visquem per aixafar el rei.

Enric IV de William Shakespeare

BURRO

La tenacitat del burro és llegendària, no obstant, en l’imaginari col·lectiu de moltes cultures és la imatge de la ignorància. A l’antiga Egipte, el burro vermell era una de les entitats més malvades que obstaculitza el viatge de l’ànima després de la mort. L’ase d’or d’Apuleu il·lustra la visió del burro com a encarnació dels instints més barroers en contraposició amb l’elevació espiritual: Lucius es transforma en ase i només quan torna a convertir-se en humà pot seguir la via a la salvació. La pintura del Renaixement va materialitzar la mandra, la tossuderia, la incompetència i l’obediència cega en forma de burro. L’expressió “orelles de burro” prové de la mitologia grega: Apol·lo va transformar les orelles del rei Mides en orelles de ruc per haver preferit el so sensual de la flauta del sàtir Màrsies en detriment de la música harmoniosa de la seva lira. En aquest sentit, els burros també van lligats a les bufonades, als carnavals, a les orgies de Dionís i a les bogeries saturnals medievals on s'invertia l'ordre convencional de les coses. L’alquímia associava l’ase amb el dimoni de tres caps —el mercuri, la sal i el sofre—, els tres principis materials de la naturalesa i veien el burro salvatge com un esperit tel·lúric i redemptor. I si hem projectat la imatge de la ignorància en un animal que tractat amb estima és perseverant i afectuós? La humilitat, bon humor i diligència del burro per plantar cara a l'adversitat el poden convertir en un company de viatge entranyable. A la Bíblia, l’ase sol ser un símbol de pau, pobresa, paciència i coratge: un ase li fa veure a Balaam que ha arribat l’àngel de Jahvé; Josep marxa en burro a Egipte per fugir de la ira del rei Herodes i Jesús fa la seva entrada triomfal a Jerusalem en burro.

“Ens enganyem constantment a través de l'orgull. Però en el fons, sota la superfície de la consciència, una petita veu tranquila ens diu que alguna cosa està desafinada.”

C. G. Jung