#34. VOLCANO / VOLCÀ

If the stillness is Volcanic in the human face / I si la quietud fos Volcànica al rostre humà

I have never seen «Volcanoes»—

But, when Travellers tell

How those old—phlegmatic mountains

Usually so still—

Bear within—appalling Ordnance,

Fire, and smoke, and gun,

Taking Villages for breakfast,

And appalling Men—

If the stillness is Volcanic

In the human face

When upon a pain Titanic

Features keep their place—

If at length the smouldering anguish

Will not overcome—

And the palpitating Vineyard

In the dust, be thrown?

If some loving Antiquary,

On Resumption Morn,

Will not cry with joy «Pompeii»!

To the Hills return!

Emily Dickinson

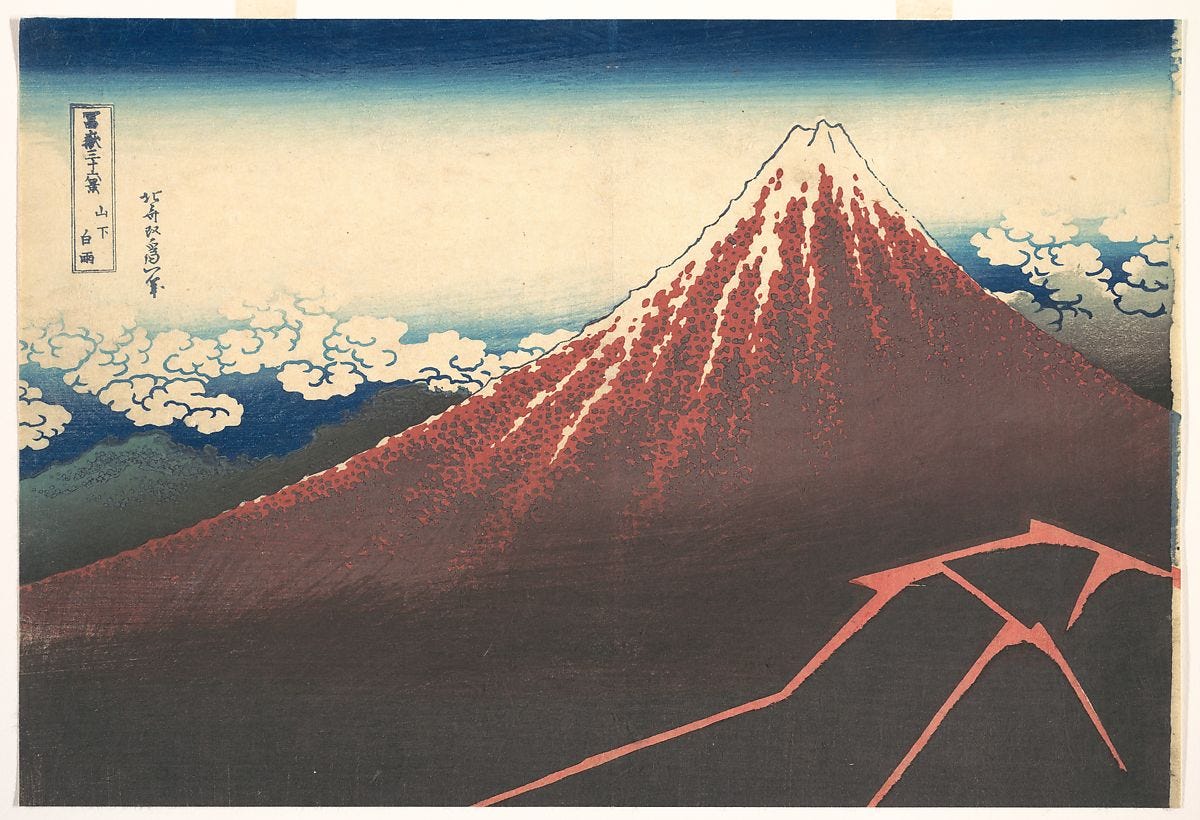

VOLCANO

Core of creation and life-destructor. To explain the origin of volcanoes, ancient civilizations spoke of subterranean forges and a supernatural blacksmith. Vulcan was the Roman god of fire, iron blacksmith and creator of art, weapons and armor for gods and heroes. Hephaestus was the equivalent in Greek mythology of Vulcan, was depicted as an ugly, lame, and very powerful god who was always working on the art of forging and his cult was related to the volcanic activity of the Aegean islands. The formidable height and presence of volcanoes make them a symbolic nexus between the earthly world and the heavenly spheres. They also represent transcendence and in various cultures they are the place of residence of the gods, either at the summit or at the core of the volcano. At the same time, fire, lava, smoke, and darkness form the prototypical image of Hell. Volcanoes generate sacred reverence and respect but are also feared for the unpredictability of their unbridled force. For the romantic movement of the 19th-century, the volcanoes and their choleric explosions were admired as if they were the zenith of connection with the sublime forces of nature.

“I felt an instantaneous affection for it and kept my hand in my pocket in order to touch it, a missal of stone. It was not until later at the airport, as a customs inspector confiscated it, that I realized I had not asked the mountain whether or not I could have it. Hubris, I mourned, sheer hubris. The inspector firmly explained it could be deemed a weapon. It’s a holy stone, I told him, and begged him not to toss it away, which he did without flinching. It bothered me deeply. I had taken a beautiful object, formed by nature, out of its habitat to be thrown into a sack of security rubble.

I took the stone from the mountain and it was taken from me. A kind of moral balance, I well understood.”Patty Smith

Mai no he vist «Volcans»

però segons diuen els viatgers,

aquestes velles, flegmàtiques muntanyes

tan quietes sovint,

porten a dins una espantosa Artilleria

foc i fum i canons

i per esmorzar es cruspeixen els Pobles

i els Homes que tenen por.

¿I si la quietud fos Volcànica

al rostre humà

quan sobre un dolor Titànic

la Fesomia se sol posar?

¿I si, a la llarga, la flamejant angoixa

no vencés,

i la Vinya que batega

per la pols s’arrosegués?

¿I si algun amable Antiquari,

el dia de la Redempció,

no cridés amb alegria «Pompeia!»

torna de nou als Turons?

Emily Dickinson

VOLCÀ

Nucli de la creació i destructor de la vida. Per explicar l’origen dels volcans, les civilitzacions antigues parlaven de forges subterrànies i d’un ferrer sobrenatural. Vulcà era el déu romà del foc, forjador del ferro i creador d'art, armes i armadures per a déus i herois. Hefest era l’equivalent en la mitologia grega de Vulcà, se’l representava com un déu lleig, coix i molt poderós que sempre estava treballant en l’art de la forja i el seu culte estava relacionat amb l’activitat volcànica de les illes del mar Egeu. La imponent alçada i presència dels volcans fan que siguin un nexe simbòlic entre el món terrenal i les esferes celestials. A més representen la transcendència i en diverses cultures són el lloc de residència dels déus, ja sigui al cim o a les entranyes del volcà. A la vegada, el foc, la lava, el fum i la foscor configuren la imatge prototípica de l’infern. Els volcans generen admiració i respecte sagrat però també són temuts per la imprevisibilitat de la seva força desbocada. Durant el romanticisme del segle XIX es van admirar els volcans i les seves explosions colèriques com si fossin el zenit de la connexió amb les forces sublims de la naturalesa.

“Vaig sentir un afecte instantani per la pedra i vaig mantenir la mà a la butxaca per tal de tocar-la, un llibre de missa de pedra. No va ser fins més tard a l'aeroport, quan un inspector de duanes la va confiscar, que em vaig adonar que no havia preguntat a la muntanya si podia o no tenir-la. Hybris, em vaig lamentar, escarpada hybris. L'inspector va explicar fermament que es podia considerar una arma. És una pedra sagrada, li vaig dir, i li vaig suplicar que no la toqués, cosa que va fer sense vacil·lar. Em va molestar profundament. Havia tret un objecte bonic, format per la natura, del seu hàbitat per ser llançat a un sac de runes de seguretat.

Vaig agafar la pedra de la muntanya i me la van agafar de mi. Una mena d'equilibri moral, ho he entès bé.”Patty Smith